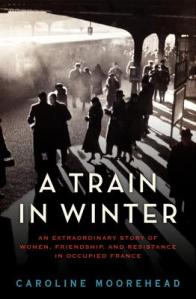

Title: A Train in Winter: An Extraordinary Story of Women, Friendship, and Resistance in Occupied France

Title: A Train in Winter: An Extraordinary Story of Women, Friendship, and Resistance in Occupied France

Author: Caroline Moorehead

ISBN: 9780061650703

Pages: 384

Release date: November 2011

Publisher: Harper

Genre: Historical nonfiction

Format: ARC

Source: TLC Book Tours/publisher

Rating: 4 out of 5

Watch a video about this book at BBC News Magazine!

In January 1943, two hundred and thirty women of the French Resistance were sent to the death camps by the Nazis who had invaded and occupied their country.

In 1941, Nazi Germany easily defeated France and struck a deal with a well-loved World War I hero, Marshal Philippe Pétain, who would lead the occupied country. In return, the Vichy government would collaborate with the occupiers.

But not every Frenchman—or woman—was as content as Pétain to collaborate with the Nazis, and a Resistance movement sprang up almost immediately. Caroline Moorehead’s impeccably detailed book follows the story of several Frenchwomen in their efforts to stymie the occupiers—and the unimaginable punishment that awaited them.

The French police, for the most part, assisted vigorously in the round-up of their fellow citizens who participated in the Resistance. One man, unsuccessfully fleeing before his execution without trial, cried out as he was caught, “Look what French police are doing to Frenchmen!”

This was a common refrain among resisters, but still their harsh treatment in the hands of their countrymen was shockingly unfettered. One French policeman, Poinsot, tortured his subjects so brutally that the Gestapo would threaten to hand other prisoners over to him if they didn’t cooperate. (At the end of the war, Poinsot was charged for the “death in deportation” of 1,560 Jews and 900 French political prisoners, as well as the execution of 285 men and “for torture so extreme people were ‘literally massacred.’”)

But if few cared about the treatment of French political prisoners, no one seemed to care about the country’s 350,000 Jewish inhabitants:

The country that had so fervently embraced the Rights of Man seemed curiously willing to sit by while one decree after another was enacted against the Jews, watching them debarred from professions, forbidden places of entertainment, relegated to the last carriages on the métro, and now herded on to cattle trucks bound for Poland.

Moorehead notes that the Gestapo had not even asked for the cattle trains; that was established on the initiative of the French railway, which charged the occupiers a set fee per transported individual.

But it is the political dissidents–and women in general–that Moorehead chooses to scrutinize. “To be young and active in France in the 1930s was to care passionately about politics,” Moorehead writes, and indeed, most of the women she focuses on were full of youthful vigor and naïve confidence.

Women in France in the thirties and forties were considered weak, less-than, a second-class citizen. Contraception was made illegal after World War I to replenish a faltering population, and during World War II, punishment for abortionists meant the guillotine. Women did not have the right to vote. But the bright side of the women’s marginalization was that they were treated differently when they were arrested. Only the most ebullient were tortured, as opposed to what seems to be the majority of the men, and Moorehead makes no mention of women being among the hundreds of untried men who were executed every time a German was attacked.

For a time, their femininity saved them. Before long, however, they faced a fate that may have been worse than death: Nazi death camps.

First in Auschwitz, the infamous extermination camp, and then in Ravensbrück, ostensibly a work camp but one in which death ruled supreme, the women faced unimaginable horrors. Of the 230 women who were deported, only 49 survived. Moorehead reports that if a woman lost her shoes—whether they were stolen by another prisoner or sucked into the ubiquitous mud at interminable roll calls—she was immediately sent to the gas chambers, “women being easier to replace than shoes.”

That any of the Frenchwomen survived is surprising. Moorehead describes the horrific treatment of the prisoners in detail, and the images of disease-ridden, rat-bitten corpses sprawled in the mud and babies drowned in barrels are stark. The survivors say that what kept them together was their selfless solidarity; they looked out for each other in ways that few of the other women at the camp did.

Of the 75,721 Jews were deported from France, a mere 3,500 returned. In comparison, nearly half of the deported political prisoners, who were admittedly treated slightly better by the Nazis, survived (40,760 out of 86,827). Possibly because so few Jews returned, they were left out of nearly all of the post-war associations planned by survivors, and for several years, the story of the death camps were written by Communists, not Jews.

Moorehead aptly describes the new pain facing survivors of the death camps:

What each of the survivors was now faced with was the question of how they would remake their lives, and how they would convey to their families what they had been through. Auschwitz and Ravensbrück, as Marie-Claude had remarked, were so extreme, so incomprehensible, so unfamiliar an experience, that the women doubted that they possessed the words to describe them, even if people wanted to hear; which, as it turned out, not many did.

The women who returned were haunted by their fallen comrades even as they tried to make new lives for themselves. Marriages—often with other deportees—were formed and then dissolved; children left behind during the war did not always warm to the strangers calling themselves their mothers.

Though the women were reluctant to speak to their children about their painful memories, they were more willing to talk to their grandchildren about it, after age had put enough distance between them and the horrific events. Yet the women never forgot the experience, and several described the incomparable closeness they still felt with their surviving friends.

In a time of unprecedented brutality and innumerable crimes against humanity, these women knew that the only thing that might allow them to survive would be solidarity. They cared for each other selflessly with little thought to their individual survival, and that, they believe, is why any of them survived the death camps.

At first, the book’s timeline sprawls, moving from one region of France to another as it introduces a seemingly endless cast of characters. But by the end, the book has moved in to focus on a handful of women as they move from prisons to camps.

I would have liked to see better references; there were many quotes, figures, and studies cited in the text that were not backed up by sources in my advanced reader copy. However, Moorehead’s heavy reliance upon interviews with survivors and their relatives gives this overlooked corner of history a new urgency. The book is dark, but rightfully so, and Moorehead somehow imparts an unshakeable faith in the ability of people to help each other survive no matter the circumstances.

Quote of Note:

“I had to hold fast to the end, and die of living.”

-One of the women prisoners

Don’t just take my word for it! Buy A Train in Winter for yourself from an independent bookstore. Each sale from this link helps support Melody & Words.

And check out what other reviewers on the tour have been saying:

November 8: Unabridged Chick

November 11: Elle Lit.

November 14: Diary of an Eccentric

November 16: Among Stories

November 16: Unabridged Chick (author interview)

November 17: Broken Teepee

November 18: Ted Lehmann’s Bluegrass, Books, and Brainstorms

November 21: Jenny Loves to Read

November 22: Picky Girl

November 23: Books Like Breathing

November 28: Reviews by Lola

November 29: Buried in Print

November 30: Savvy Verse & Wit

December 1: In the Next Room

December 2: Wordsmithonia

December 2: Books and Movies

December 5: Take Me Away

Categories: 4-4.5 stars, Book Reviews

What a powerful book! Sometimes I wonder what I would have done in such a situation. I can only hope I’d have the same character as these women had.

Thanks for being on the tour! Your review is riveting!

LikeLike