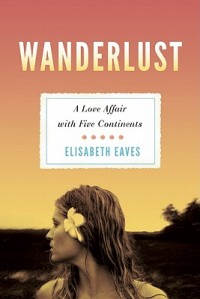

Title: Wanderlust: A Love Affair with Five Continents

Title: Wanderlust: A Love Affair with Five Continents

Author: Elisabeth Eaves

ISBN: 9781580053112

Pages: 303

Release date: May 2011

Publisher: Seal Press

Genre: Travelogue; memoir

Format: Paperback

Source: TLC Book Tours

Rating: 1 out of 5

Quick and dirty: Wanderlust is heavy on the lust.

Some compare it to: Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert

Possible theme song: “You Don’t Know What Love Is” by the White Stripes

Read this book if: You like reading about sexual misadventures all around the world.

To say that Elisabeth Eaves has caught the travel bug is to put it lightly. She is obsessed with seeing new places and meeting new people. She begins her travels by babysitting for a summer in Spain, where she has a short fling with a young waiter named Pepe.

Next, she studies abroad for a year in Egypt, with a side trip to Yemen. Though she recounts almost constant harassment from men in the Middle East, she also acknowledges that her nationality grants her a different treatment than those of her own sex. She comments of her time in Yemen, “As foreign women, we were a sort of third sex, allowed, like Ottoman eunuchs, to pass between two worlds.”

At the end of the year, Elisabeth returns to school in Seattle and a boyfriend, Graham, who works at a ski lodge a few hours away. Elisabeth decides to intern with the State Department in Pakistan the next summer, and she and Graham break up. “I’d made a choice,” she writes, “and it was not to try for love, with all its risk of pain, but to travel.”

Hence begins a cycle that she is unable to break for the rest of her narrative.

After a summer spent in Pakistan, she settles in with Stu, her next boyfriend, in Seattle. The two buy a rundown house and focus on fixing it up. They lead insular lives, with few friends or hobbies other than feathering their nest. After a year, he proposes and she accepts.

But Elisabeth is unhappy in Seattle, though she never tells Stu. She says, “I felt out of place, maybe even more than I had in Egypt or Pakistan. It was harder to know who I was in Seattle. Anywhere exotic, as a permanent stranger, I could define myself against everything around me.”

She revels in, or, at least, never seeks to reconcile, the sharp contrast between her outer life—where she is the perfect fiancée who contorts herself into the kind of woman she thinks her boyfriend would like—and her inner life—where she tires of the claustrophobic responsibility of a two-way relationship.

She yearns to discover herself on another continent, free from mortgages and marriage:

There are lives—so many—that I hadn’t experimented with. What if I was meant to be an aid worker, a dive instructor, a spy? What if I was meant to be a writer in New York? And forget even what I was meant to be. What would it feel like to just wander the world, free of all responsibility, knowing I could stand on my own two feet? I resented Stu for keeping me from all those other possible lives.

She begins sneaking money into a secret bank account, and announces to Stu that she needs to travel for a few months in Australia before they get married. Two months turn into fourteen, and Elisabeth breaks up with Stu one night over the phone.

One dalliance in Australia is named Jason, a young man who is perpetually high and unemployed. Elisabeth decides to seduce him mostly out of boredom. At one point, when Jason offers to give her a massage, the book veers into Harlequin territory:

I moaned and lolled my head, and rolled it to the side so that my cheek touched his hand. The he put his fingers in my mouth. He might as well have pressed a trigger. Now I’d want him inordinately for that one little act. I’d want him until my desire either dissipated or was denied.

She is often very open about her sexual encounters, even to a fault. But at the same time, I get the impression she’s hiding something. She says that she wanted Jason, but the reader only finds out that she was successful several pages later, as a side note. As a result, I felt myself straining to read between the lines of every interaction she has with men, often concluding that she sleeps with most of the guys she mentions. Being forced to doubt her as both a person and a reliable narrator doesn’t make her a very sympathetic main character.

Elisabeth mistakes lust for love time and again without seeming to realize it. When she meets another Australian, Justin, the two become inseparable. Here Eaves seems shockingly naïve in matters of love and trust:

I hadn’t loved Justin when I first met him; I’d wanted to keep him at arm’s length. But then I grew comfortable, and trusting, and suddenly I desired him, and once I desired him I loved him. I also still loved Stu. Justin loved me. . . . Do people get married, I wondered, because all this volatility goes away, and they finally know, without a doubt, that they only love one person? Or do they get married out of hope that they can rise to the occasion, and then, if other feelings arise, tame them into submission?

She decides to get back together with Stu, who has sailed to New Zealand and set up quite a nice life as a nautical carpenter. He was dating a woman who fades off the scene, of whom Eaves confidently writes, “It wasn’t a competition for his affections; I was the one who compelled him.”

But, of course, she can’t stay with him for long. Again, Elisabeth’s immature view of love and responsibility took me aback. She writes,

I saw my love for Stu as now thoroughly tarnished, not because we’d hurt each other or slept with other people or spent time apart—all those usual suspects made no difference. It was tarnished because now it was wrapped up in obligation. Obligation, of course, is what binds marriages all over the world. You get into financial dependence, kids, intertwined lives, and you can’t get out. Mutual obligation is the norm, the glue. Loss of freedom is the point, the thing that evens out the vagaries of the heart. I didn’t understand any of that.

To argue that responsibility and commitment kill love is to display an inept grasp of it. True love is not destroyed by intertwined lives—on the contrary, it is strengthened by it.

Her lack of regard for the feelings and well-being of others is shocking. I’m not just talking about the many times she cheats on or lies to her sexual partners; at one point, she lies about her sailing experience to a couple looking for a deck hand, and Elisabeth finds herself in the midst of a huge ocean storm. Wouldn’t it have been nice for her employers if they’d had an experienced hand to help out?

Once back in Seattle with Stu, she again weasels out of her responsibilities with him, this time permanently: “Slowly, over the year between New Zealand and New York, I convinced Stu to buy me out of the house, and we said good-bye.” One only hopes he didn’t entertain any desire to return to his successful career in New Zealand.

In New York, Elisabeth begins a relationship with Paul. When she breaks up with him after two and a half years and he cries, she claims to be just as anguished—not for being the cause of his bewilderment and pain, but for closing the door on “a possible life I’d entertained.”

She finds a new man, called only “the Englishman.” The only thing we learn about the two months’ vacation she had with him in Mexico is what they ate and how often they had sex. (Answer: Avocados and very often.) He is more like her than any other man she has met, so, of course, he ends up leaving her.

When she settles down with the next man, Dominic, at the age of 30, she only does so because her debts have mounted and she needs someone to take care of her.

While with Dominic, she begins a phone-relationship with Justin, back in Australia. “There’s no downside,” she reasons. “It’s like hearing from an old friend, with the added frisson of desiring and being desired, but with no consequences.” (I bet Anthony Weiner would disagree.)

Early in their relationship, Dominic asks Elisabeth how many people she has slept with—a reasonable question, to me, a product of the condom generation. But she sees it as “a sign of an anxious, visceral sort of sexism that I wanted nothing to do with.” So she lies, and resents him thereafter for asking.

She uses feminism as an excuse for selfishness and infidelity, claiming that “unlike women of an earlier era, I wasn’t raised to subordinate my desires to the needs of others.”

This kind of misguided feminism comes up again when she concludes that she “forgot to make a life . . . to get a steady job, or belongings, or a family of my own . . . to choose somewhere to be.”

She continues, “I forgot to the things that, despite decades of feminism, I felt the niggling weight of, in a way that I imagine men don’t.” If one is to believe Eaves, men never experience the need or desire to get a job, assemble belongings, make a family, buy a house. (Even Neil Strauss needs to live somewhere.)

Perhaps what irritates me most is her smug ignorance and rejection of what she calls “quotidian life.” She doesn’t understand why anyone would want to settle down – they’re only settling, she reasons. “I knew in theory that a grown-up chooses to leave her highs behind, in favor of a stable life,” Eaves writes, without acknowledging that, perhaps, there can be highs other than forbidden trysts in dirty hostels with strange men.

Eaves is terrified of seeming vulnerable, of not appearing tough enough. She wants to conquer men before they can conquer her. While men may aim for sexual conquests, however, Eaves needs romance. She needs men to fall in love with her—to need her.

There is nothing wrong with craving exotic adventure, but she hurts those whom she claims to love. She is desperately afraid of becoming average, of trusting another person with her feelings, of discovering who she really is. So she flees again and again.

But she brings with her narrative no self-awareness, no sense of maturity or wisdom. As a reader, I want to see change, revelation, epiphanies—anything but an endless string of affairs. There is no arc, no continuous theme or idea to tie these disparate anecdotes together, except her insecurity and desire to hide in sex.

“The traveler always betrays the place,” Eaves writes upon leaving Spain. And in her world, the traveler also betrays the lover.

But don’t just take my word for it! Check out these reviews:

Monday, June 13th: English Major’s Junk Food

Tuesday, June 14th: Confessions of a Book Addict

Friday, June 17th: Amused by Books

Wednesday, June 22nd: Books Distilled

Thursday, June 23rd: Life in Review

Monday, June 27th: Nomad Reader

Wednesday, June 29th: Regular Rumination

Thursday, June 30th: Birdbrain(ed) Book Blog

Tuesday, July 5th: Chaotic Compendiums

Thursday, July 7th: The Girl from the Ghetto

Tuesday, July 12th: Books Are My Boyfriends

Thursday, July 14th: Joyfully Retired

Categories: 0-1.5 stars, Book Reviews, DC Books, Authors, and Bookstores

I had many similar reactions to this one. I really liked the first third or so, but I agree with you, I wanted an arc or some resolution. With an introduction so intriguing, how could there be no conclusion? The action didn’t even bend back to the introduction. I’m still formulating my thoughts on this one, as I loved parts of it and found other parts dull.

LikeLike

Yes – another reviewer observed that it’s almost as though Eaves becomes a different person on each continent. I found the parts about traveling in the Middle East very interesting – women do face very different challenges when they travel! But the rest was a little too strange for me.

I think perhaps the subtitle is a little misleading; “Love Affairs on Five Continents” might be more appropriate.

LikeLike

Melody, thanks for a very thorough analysis. I like the quotes you chose to highlight and I think your review leaves a lot of room for readers to make up their own minds about whether or not this one would be for them. Thanks so much for being on the tour!

LikeLike

THANK YOU. Yes. This is exactly how I feel. This was billed as a travel memoir, but really it was just a list of men. I also hated how every other female character was ugly or stupid or in her way or betrays her. She never portrays another woman in a good light, not even her best friend.

LikeLike

I’m glad you enjoyed the review! I also noticed her strange behavior toward other women, beginning with pointedly referencing the American girl she meets in Spain as chubby or overweight.

This contributed to my sense that Elisabeth (the character) is an unreliable narrator; her perceptions of the women in her life color her account of her interactions with them–particularly with her best friend, as you mention. Elisabeth can’t seem to understand why Kristen wouldn’t want to stay in Australia indefinitely, and her sense of betrayal is clear.

It all makes her strange appeals to feminism seem all the more off base.

LikeLike

Reading “Wanderlust” for me was like having a conversation with a very delusional friend. I was compelled by a need to constantly want to smack some sense into her. It’s true, she’s a very selfish person and her path is a proof to that. At the end of my reading however, I came to term with two things. The first is that Eaves is very unapologetic about her choices and yet, very aware she’s made mistakes. The second, made me wonder about selfishness, because it is something that our Western society condemns and yet, in her case, allowed her to realize her dreams, go for the things she wanted. Because if a part of me looked down on her morals, another part of me envied her for being able to do something I can’t allow myself to. I guess it comes down to saying I’m fascinated by what I don’t and can’t understand. With perspective, I’m no longer sure I hated that book, the same way I can’t help but love a very frustratingly unalike friend.

LikeLike

That is such a great point! I really agree. The reason my review is so long and detailed is because I grappled with these very issues. Although her selfishness is off-putting, her bravery is commendable.

LikeLike

Is it just me… This book made me want to revisit my old friend Kundera and his “Unbearable Lightness of Being”…

LikeLike

Actually “frenemy” would be more exact.

LikeLike

Just stumbling onto this review now because I myself just finished reading this book. I am so happy you were able to articulate many things I was feeling while reading this but couldn’t quite formulate for myself! Thanks so much for this review. I would also like to add that one thing that especially frustrated me (which I guess parallels with your opinion that she is not a trustworthy narrator) – on top of the focus on infidelity/callousness towards the men she was with – is that she never really commented or appreciated her privilege to travel as much as she did, or how she was even able to. She condemns so many people who live “normal” lives, refusing to travel, as if they even have a choice to. She doesn’t recognize her need for other people to fall back on when she has no money left to travel; she just resents them but still uses them anyway until she can leave again.

Sorry if this comment is so late in the conversation, but it’s all fresh for me since I just read the book!

LikeLike

hey there and thank you for your info – I’ve certainly picked up something new from right here.

I did however expertise several technical issues using this site, as I experienced to reload the web site many times previous to I

could get it to load properly. I had been wondering if your web

hosting is OK? Not that I am complaining, but slow loading instances times will very frequently affect your placement in google

and could damage your quality score if advertising and marketing with Adwords.

Anyway I am adding this RSS to my email and could look out

for much more of your respective interesting content.

Make sure you update this again soon.

LikeLike

I’d like to find out more? I’d want to find out some additional information.

LikeLike

A fascinating discussion is definitely worth comment. There’s no doubt that that you should

publish more about this topic, it may not be a taboo subject

but generally folks don’t speak about such subjects.

To the next! Kind regards!!

LikeLike